‘Everyone is entitled to his own opinion, but not his own facts.’ Attributed to Daniel Patrick Moynihan

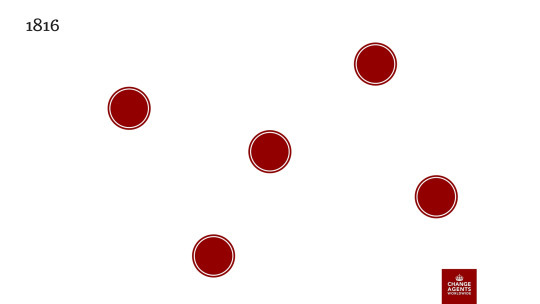

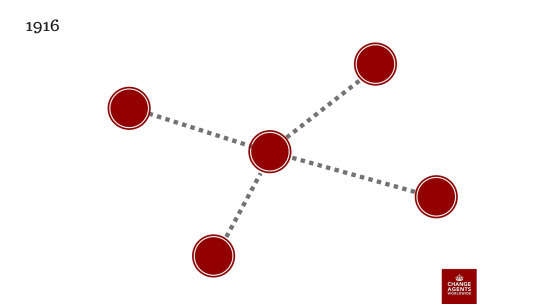

Once debate was a contest of opinions. There may have been disputes around the edges about the facts but the common ground was clearly agreed.

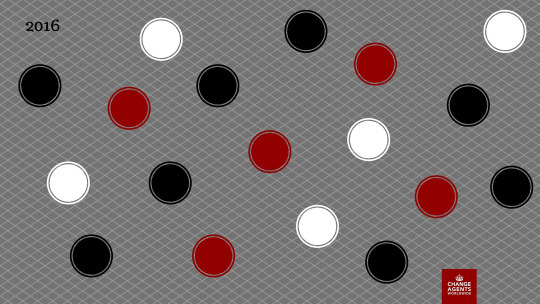

Increasingly we see the facts themselves as the subject of a debate. Each side girds itself with its own view of the world and the facts. Read the paper, listen to the radio, watch the television or study social media and you will see people put forward the facts that justify their position and deny all others. Without common context, any hope of agreement or resolution is slim.

‘Lies, damn lies and statistics’ 19 Century British Political Phrase

The growing availability of data in our world and the increasing ability to connect a niche audience for your data is only likely to make this an increasing challenge. Even if we put aside the patently false, selective use of data can tell almost any story. Fact checking can only go so far before it meets differing references periods, unclear definitions, crossed purposes and misinterpretation.

Our focus on science, political science, economics and scientific management has been part of creating an intense focus on the idea that the answer is in the data. However, data confirms hypotheses and arguments. We cling to data as the trump card in debate. A wide choice of data enables many competing approaches to be confirmed. As we deal with ever more complex and more global systems, we are reaching a point where a single data story can no longer be the simple answer.

“I would not give a fig for the simplicity this side of complexity, But I would give my life for the simplicity on the other side of complexity.” Attributed to Oliver Wendell Holmes Snr

We need to accept that no argument will be won with a data point or a trend, however appealing that simple approach may be. As reassuring as they are our own facts are useless in society. Allowing ourselves to be divided into tribes with their own facts is far too unproductive and dangerous to our future. Civil debate begins by finding the common ground and creating a growing shared context. That takes leaders who can explore what is shared rather than focus on differences of facts.

We also need to embrace a greater share of the complexity of life in our global interconnected world. We can no longer rely on the simple answers. That trend may lead only to a local maximum or miss some wider ramifications of the decision. We need to go hunting together in the complexity, experimenting and genuinely debating the paths forward together. Continuing open dialogue that builds a shared common ground is the path to a new contest of ideas on the other side of complexity.