Photo: Shannon Tipton (@stipton) votes to change the status quo at #EdutechAU.

As our organisations look to adapt to a connected world, learning will need to play a far more strategic role. Learning functions need to move from being order takers to change agents in the transformation of leadership, culture, work and organisational structures. After all, we won’t achieve our strategic goals if people don’t have the capabilities we need.

Changing the Learning Game

Change was at the forefront of the agenda of the EdutechAU workplace learning congress this week. There wasn’t a speaker or a panel that did not seek to address how organisations were using learning to manage change. These changes were hardly minor. For example, in the case studies alone we had examples of:

- Medibank building capability for workplace culture and wellness issues in an activity based workplace through experiential & mobile learning

- the Australian Electoral Commission rethinking its entire employee development cycle between elections with a goal of focusing more on the why and how than the what.

- Coca Cola Amatil building the capability of its operations teams to learn for themselves and from each other without training

- AT&T using the scale of MOOCs to retrain its global workforce into strategic capabilities and out of declining roles

- using learning and the learning function to change culture at Northern Lights

In all the talks were the key drivers of transformation for businesses and that learning is seeking to better leverage. All our work is becoming:

- more connected and social

- more open and transparent

- more automated

- more flexible

- more complex

- more knowledge based

- more dependant on culture

- more demanding in terms of speed, quality, efficiency, effectiveness, etc

These changes present an opportunity and a threat to learning function everywhere. Learning has opportunities to be more strategically valuable, reach more people than every and in far more engaging ways. Learning has the potential to do and control less but achieve far more by moving from design and delivery to facilitating learners to pull what they need. At the same time, the threat to learning is that both learners and management has far more available from social channels external to the organisation and the participatory culture available in those networks often more agile and even more engaging.

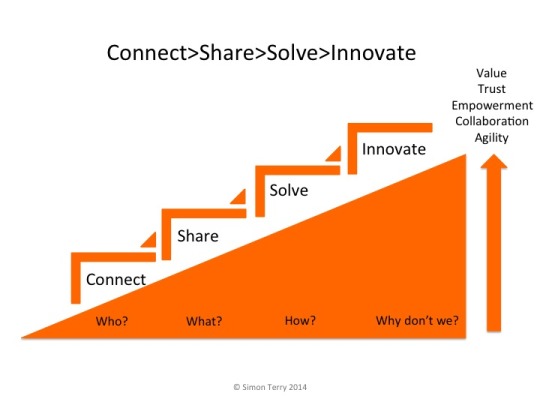

To leverage these challenges for opportunity, learning needs to move from an order taker for training programs to a strategic agent of change. The new challenge for learning is to rethink how they set about enabling the network of people in the organisation to build key capabilities, to help people build constructive culture and to change the way managers manage and leaders lead. The answer will be less about control and specific training programs and tools and more about how learning works in a system of capability building that reinforces the organisation’s goals and uses the best of what is available in learning, in the social capital of the organisation and its networks.

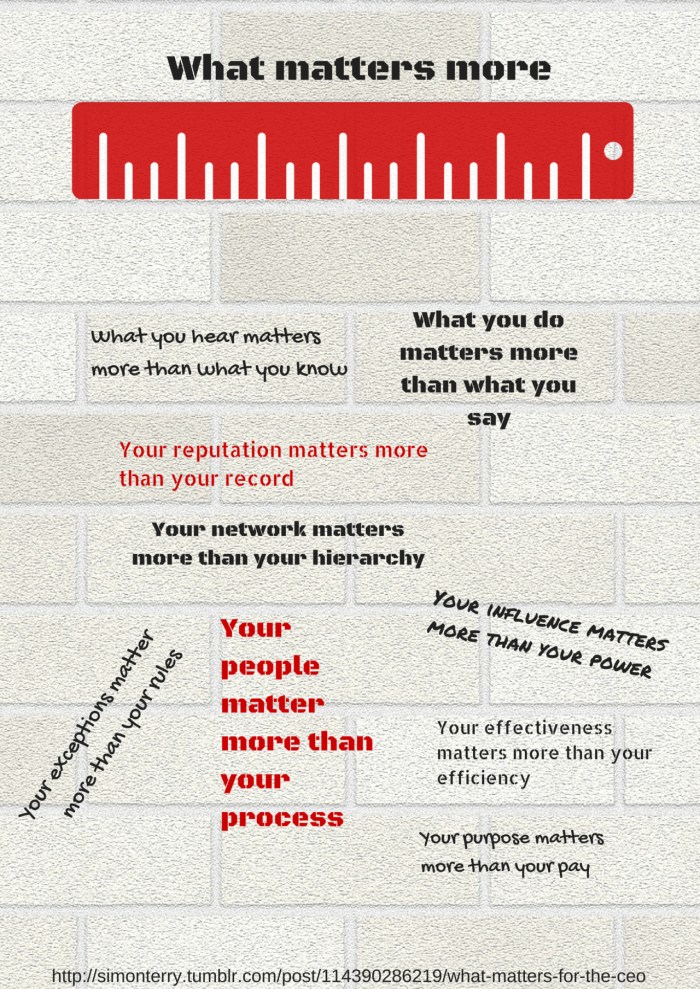

Becoming More Human

Speaker after speaker highlighted another key element of this transformation. As work becomes more personal and more human, there is also a need for learning to lead that change too. Learning functions need to consider how they design human experiences, faciltitate human networks and realise human potential, even anticipate human emotions. The future of work puts a greater demand on design mindsets, systemic approaches and the ability to weave together networks of experiences and people in support of capability building in the organisation.

This human approach extends also to how learning works. These kinds of programs need experimentation, learning from failure and adaptation over time as the people and the organisation changes. Learning will need to role model and shape leadership as a vehicle for realising the human potential of each individual, organisation and each network.

The Obstacles are The Work

EdutechAU was not an event where people walked away with only a technique to try on a new project. There were undoubtedly many such ideas and examples from social learning, to MOOCs, to experience design & gamification, to networked business models, to simulations and other tools. However, the speakers also challenged the audience to consider the whole learning system in and around their people. That presents immediate challenges of the capability of the learning team and their support to work in new ways. However, those very challenges are part of helping the system in their organisation to learn and adapt. The obstacles are the work.

Thanks to Harold Jarche, Alec Couros, Marigo Raftopoulos, David Price, Ryan Tracey, Shannon Tipton, Emma Deutrom, Joyce Seitzinger, Con Ongarezos, Peter Baines, Amy Rouse, Mark L Sheppard and Michelle Ockers for their contributions to a great event.